Conservation of Wildlife

A retrospective, nostalgic, tribute to the researchers and environmentalists involved in recording the profiles and details of the management status of national parks and sanctuaries in India.

Between 1984 and 2002, a team of mostly young (and some not so young) wildlife enthusiasts and researchers studied the wildlife protected areas in India and initially produced a series of directories and an assessment of their management status and, from 1993, a series of ecodevelopment plans and discussion papers. For many of us this became our enduring, if not our main, research passion during these years.

We mostly worked out of the Indian Institute of Public Administration, New Delhi, in close association with the voluntary group Kalpavriksh. Most of the team members were either already, or soon became, members of “KV”, as it is popularly known.

In the early years, there was also a robust association with the Bombay Natural History Society, mainly through Dilnavaz Variava, who was the initiator of this genre of wildlife management research in India. In fact, it was she who was originally commissioned, in the early 1980s, by the erstwhile National Committee on Environmental Planning (NCEP), Government of India, to undertake a survey of national parks and sanctuaries in India. As a precursor to the proliferation of reports and discussion papers, she and I put together a directory of national parks and sanctuaries in India, in 1985. Copies of this mimeographed document were circulated at the 25th session of the IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas (CNPPA), held in the Corbett National Park, in early 1985. It briefly described each of the 300 NPSs existing then in India: consisting of 53 national parks and 247 sanctuaries. Though I am a co-author, the lions share of work was done by Dilnavaz. To modify a famous expression: she was the lioness and I just had the privilege to roar along with her…

Dilnavaz and I also worked together, along with Ashish Kothari and Pratibha Pande, in researching and drafting the first of the management status reports, in 1989. Unfortunately, mainly because she lived in Mumbai and had a host of other responsibilities, Dilnavaz could not, much to our loss, keep up her active association with the work that she had initiated.

Apart from Dilnavaz, the two other leading lights in this somewhat new and innovative approach to studying wildlife management in India, were Ashish Kothari and the late Pratibha Pande. Ashish was the master of all trades and more than ably ran much of the project. Pratibha, apart from livening up our daily life in her inimitable cheerful style, was an avid wildlifer and birdwatcher, and an exceptionally talented artist, as witnessed by her numerous sketches illustrating the directories.

She was involved in developing and drawing the maps for these publications, a task in which she was ably partnered by Raman Mehta. Raman was also our inhouse computer expert. He was mostly responsible, in the mid-1980s, for teaching all of us how to use computers: PC XTs and Word Star to start with, and worked hard to help Ashish overcome his initial dislike and suspicion of computers.

Some of the other enthusiasts and researchers, without whose involvement this work would never have been done, included Amita Bedi, Anita Lal, Farhad (Bingo) Vania, Jaya Menon, Joanne Carneiro, Maneka Singh, Pallava Bagla, Pallav K. Das, Ranjit Lal, Rupa Desai, and Sunita Rao, among many others.

In early 1990s some new researchers joined the team, with fresh perspectives and different working styles. These included senior members like Vasumathi Sankaran, the senior most among us in age, and a geographer to boot, Tara Gandhi, a biologist and ecologist, and Nandan Maluste, who was director of a leading advertising agency in Mumbai, till he joined the IIPA team,.

The younger recruits included, Amita Baviskar, Angana Chatterjee, Archana Prasad, Arpan Sharma, Avanti Mehta, James Pochury, Johara Shahabuddin, Miloon Kothari, Prabhakar Rao, Ravi Bhalla, Ritwick Dutta, Saloni Suri, Salim Ahmad Quereshi, Sultana Bashir, and Vishaish Uppal. A full list will be found in the beginning of each research report.

To me, personally, apart from all of them, great support came from Theodore Baskaran, who first educated me, in the mid-1970s while we were both in Shillong, about the finer points of wildlife management, and fuelled my enthusiasm for bird watching. I still have painful memories of driving my jeep through the forests of Meghalaya, Mizoram, and Nagaland, with Baskar sitting next to me on the front seat. Every time he spotted a bird, or heard a birdcall, he would excitedly squeeze my arm hard till I braked and allowed him to jump out and focus his binoculars on his feathered friend. Those were long, painful, but educative drives and I consider Baskar to be the foremost of my environmental gurus.

Soon after I shifted to Delhi, in 1980, I met W.A. (Alan) Rodgers (tragically now deceased), who was an FAO consultant with the Wildlife Institute of India. He then took up from where Baskar had left off. Alan was a trained biologist who had also managed wildlife protected areas in East Africa before becoming an FAO consultant in India.

For the next decade or so we travelled many parks and sanctuaries together, and he taught me much about ecosystems and how they needed to be conserved. He was also a keen student of the social and administrative factors that impacted wildlife conservation, and we spent many hours discussing these. He critiqued our various draft reports and I still have copies with his comments in red ink, in a large not-to-be-missed handwriting. Having had a scientific education, he believed in certainties and “facts”, while my background in philosophy made me much more tentative. Therefore, I often prefaced my findings and conclusions with “I think” or “I feel”. I still remember receiving back one such draft, which perhaps had too much “tentativity”, with his large handwriting scrawled across the page in red: “We must stop Shekhar Singh from feeling around so much!!”

Some of the other people who rendered critical support and advice in this endeavour included the late Mr. BB Vohra, formerly chairperson of the NCEP, the late Mr. R.Rajamani, Mr. Samar Singh, Dr. MK Ranjitsinh, and Mr. Kishore Rao of the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India, and Mr. HS Panwar of the Wildlife Institute of India. The Ministry of of Environment and Forests, Government of India, and the Wildlife Institute of India, financially supported much of this work.

Though perhaps now of only historical interest and value, these publications represent a research genre which no longer seems to be popular. Therefore, the least one hopes for is that by circulating these volumes now (especially when many people have time on their hands to read low priority things), someone will get provoked into taking up the challenge and re-examining the status of these protected areas, as they are today, thereby giving us an idea of trends over time and prospects for the future.

Shekhar Singh

New Delhi 2021

Documents under Conservation of Wildlife

1984 - Guidelines for Village Adoption

Describes the methods and criteria to be used to adopt villages adversely affecting wildlife protected areas, with the objective of gradually helping them to develop the alternate economic opportunities and natural resources that would minimise their impact on the protected area. This was a precursor to the ecodevelopment approach described later. Download1988 - National Zoological Park, New Delhi - Perspective Plan

1988 - National Zoological Park, New Delhi - Perspective Plan Download1993 - Joint Protected Area Management: Some Policy Issues

An input into the national discussion on incorporating lessons, from the successes in the joint forestry management (JFM) experience, into the management of wildlife protected areas (PAs) in India. Download1995 - Human Population, Biodiversity & Protected Areas- Science & Policy Issues

1995 - Human Population, Biodiversity & Protected Areas- Science & Policy Issues Download1999 - Assessing Management Effectiveness of Wildlife Protected Areas in India

1999 - Assessing Management Effectiveness of Wildlife Protected Areas in India Download1999 - Protecting Biodiversity Under the Wildlife Protected Area System in India: A Status Report

1999 - Protecting Biodiversity Under the Wildlife Protected Area System in India: A Status Report Download2000 - Book Review - Wild About Nature

Review of the book The Dance of the Saurus: Essays of a Wandering Naturalist, by S.Theodore Baskaran Download2002 - Evaluation of the Existing Schemes of Paying for Loss & Damage Caused by Wild Animals

2002 - Evaluation of the Existing Schemes of Paying for Loss & Damage Caused by Wild Animals Download2008 - The Forest Rights Act 2007: Implications for Forest Dwellers and Protected Areas

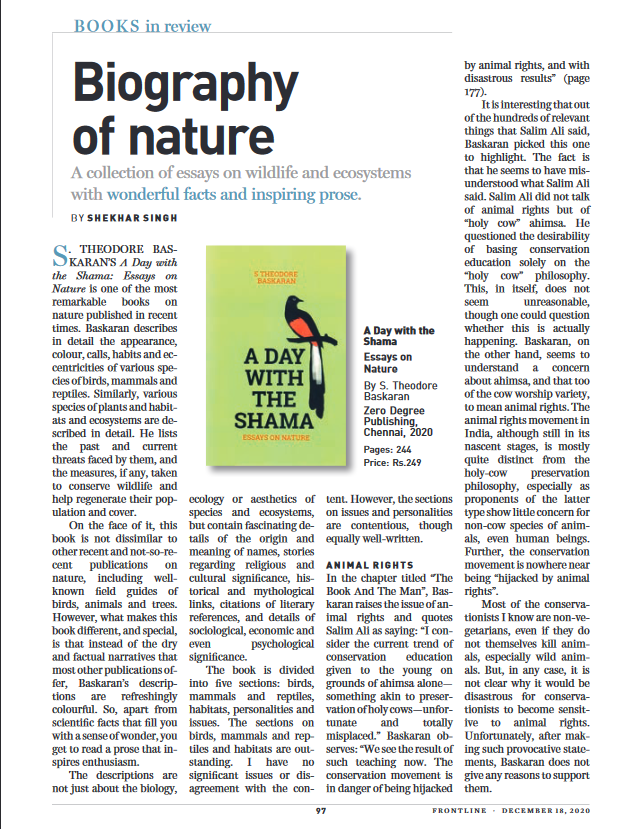

2008 - The Forest Rights Act 2007: Implications for Forest Dwellers and Protected Areas Download2020 - Book Review - Biography of Nature

A review of the book "A Day With the Shama" by eminent wildlifer S.Theodore Baskaran. DownloadConservation of Wildlife :

Relevant Unpublished/Out-of-print Documents by Other Authors

1962 - Report on the National Parks and Wildlife Sanctuaries (Equivalent Reserves) in India - EP Gee

Among the earliest, if not the first ever, report on the wildlife protected areas in India, presented to the First World Conference on National Parks. Download1987 - Record of Discussion on Role of NGOS in Wildlife Conservation in India

1987 - Record of Discussion on Role of NGOS in Wildlife Conservation in India DownloadFirst Survey of National Parks and Sanctuaries in India : 1984-1994

Conservation of Wildlife - First Survey of National Parks and Sanctuaries in India : 1984-1994

First Survey of National Parks and Sanctuaries in India

The initial work taken up by the IIPA team, in 1984, along with many partners and collaborators, was to survey and record the profiles and management status of wildlife national parks and sanctuaries in India. Though an effort was made to cover all the PAs in India, a few did not respond.

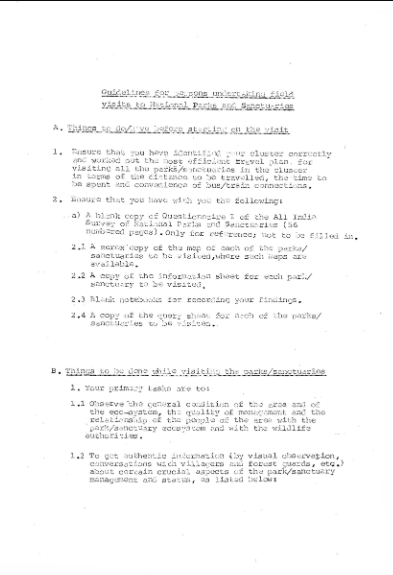

The survey was carried out through two sets of questionnaires, one to be filled up by the protected area manager for each PA, and the second by the chief wildlife warden of each state/union territory. Secondary data was surveyed and a sample of PAs in each state/UT were visited. Discussions were also held with various stake holders and other knowledgeable people. Copies of the questionnaires are included in this collection and details of the methodology are given in the reports.

Out of this process came two types of publications. First, directories of PAs, at national and state level, which described the profile and management status. Second, an issue wise analysis of the PAs in the country, prepared in 1989, the first survey, and 2000-03, the second survey.

Based on these surveys and reports, working papers were also written to discuss the findings.

Shekhar Singh

February 2021

Documents under Conservation of Wildlife - First Survey of National Parks and Sanctuaries in India

1984 - Questionnaire-1 - All India Survey of National Parks and Sanctuaries

1984 - Questionnaire-1 - All India Survey of National Parks and Sanctuaries View Download1984 - Questionnaire-II - All India Survey of National Parks and Sanctuaries

1984 - Questionnaire-II - All India Survey of National Parks and Sanctuaries Download1985 - Directory of National Parks and Sanctuaries in India

1985 - Directory of National Parks and Sanctuaries in India View Download1989 - Management of National Parks and Sanctuaries in India - A Status Report

1989 - Management of National Parks and Sanctuaries in India - A Status Report Download1989 - Study on Management of Wildlife Protected Area in India - Qestionnaire - A

1989 - Study on Management of Wildlife Protected Area in India - Qestionnaire - A Download1990 - Directory of National Parks & Sanctuaries in Himachal Pradesh

1990 - Directory of National Parks & Sanctuaries in Himachal Pradesh Download1990 - DRAFT Directory of National Parks & Sanctuaries in Gujarat

1990 - DRAFT Directory of National Parks & Sanctuaries in Gujarat Download1991 - Directory of National Parks & Sanctuaries in Andaman & Nicobar Islands

1991 - Directory of National Parks & Sanctuaries in Andaman & Nicobar Islands Download1991 - India's National Parks - A Management Profile

1991 - India's National Parks - A Management Profile Download1994 - Directory of National Parks and Sanctuaries in Karnataka

1994 - Directory of National Parks and Sanctuaries in Karnataka DownloadDocuments under Conservation of Wildlife - First Survey of National Parks and Sanctuaries in India :

Relevant Unpublished/Out-of-print Documents by Other Authors

1989 - Book Review - Management of National Parks and Sanctuaries in India

A review, by eminent wildlifer S. T. Baskaran, of the book “Management of National Parks and Sanctuaries in India” (see above)Download

1995 - Book Review - Directory of National Parks and Sanctuaries in Karnataka

An anonymous review in the “Indian Express”. DownloadEcodevelopment : 1993-2003

Conservation of Wildlife - Ecodevelopment : 1993-2003

Ecodevelopment

Unfortunately, much before we could finish directories for all the states, many of us got diverted to developing “ecodevelopment” plans for managing human nature interaction in and around PAs. This was not only an urgent need but, for the first time, we were going beyond just recording and evaluating the status of wildlife protected areas, and actually attempting to do something about protecting them better. Consequently, we only managed to complete the draft of one more directory, for Gujarat (1990), which was never finalised or published, and only a photocopy of a dot matrix computer printout survives.

The “ecodevelopment” approach was pioneered by the legendary wildlifer H.S. Panwar, when he was director of the Kanha National Park in Madhya Pradesh, in the 1970s. It involved PA management in a manner such that both the local wild life and local human populations benefitted, or at the very least, did not adversely affect each other while fulfilling their basic needs. This approach was increasingly being recognised as the optimal approach for resolving the conflicts that arose when local populations were prevented from using the resources of PAs, to fulfil their economic and natural-resource needs. Essentially, ecodevelopment involved investing in developing viable income and natural-resources alternatives for the local people so that they would be more able and willing to respect the restrictions that PAs imposed upon them.

The Government of India (GoI) decided, in 1993, to approach the World Bank, as a part of the Forest Research Education and Extension Project (FREEP), for financial support to initiate an ecodevelopment project in two PAs. Breaking from the tradition of the World Bank developing the project document through its own team, the GoI approached the IIPA team to develop the project documents for Great Himalayan National Park and the Kalakad Munduanthurai Tiger Reserve.

These were developed in 1993 and revised in 1995-96, and the original and revised project reports are included in this collection. In 1994, the IIPA team was again approached by GoI, this time to develop a much larger ecodevelopment project covering six protected areas, for funding by the Global Environment Facility (GEF). The development of the project report was supported by the United Nations Development Programme.

Shekhar Singh

February 2021

Documents under Conservation of Wildlife - Ecodevelopment

1993 - Biodiversity Conservation Through Ecodevelpment - GHNP & KMTR

1993 - Biodiversity Conservation Through Ecodevelpment - GHNP & KMTR Download1994 - Biodiversity Conservation Through Ecodevelopment - An Indiacative Plan for Eight PAs

1994 - Biodiversity Conservation Through Ecodevelopment - An Indiacative Plan for Eight PAs Download1994 - Joint Protected Area Management: Some Policy Issues

This was an input to the then ongoing discussion on the feasibility of “joint protected areas” as a future strategy for wildlife conservation.The effort was to learn from the successes and failures of the joint forest management strategy. Download

1995 - Human Nature Interaction In and Around National Parks and Sanctuaries

1995 - Human Nature Interaction In and Around National Parks and Sanctuaries Download1995 – Integrated Conservation Development Projects for Biodiversity Conservation – The Asia Pacific Experience

1995 – Integrated Conservation Development Projects for Biodiversity Conservation – The Asia Pacific Experience Download1995 - Periyar Tiger Reserve - An Assessment

1995 - Periyar Tiger Reserve - An Assessment Download1995 - Sariska Tiger Reserve

1995 - Sariska Tiger Reserve Download1996 - Great Himalayan National Park

1996 - Great Himalayan National Park Download1996 - Rajaji National Park

1996 - Rajaji National Park Download1997 - Biodiversity Conservation Through Ecodevelopment - Planning & Implementation Lessons from India

1997 - Biodiversity Conservation Through Ecodevelopment - Planning & Implementation Lessons from India View Download1998 - Ecodevelopment in India - Some Concepts and Issues

1998 - Ecodevelopment in India - Some Concepts and Issues Download1999 - Ecodevelopment - Many Questions, Some Answers

1999 - Ecodevelopment - Many Questions, Some Answers DownloadConservation of Wildlife - Ecodevelopment :

Relevant Unpublished/Out-of-print Documents by Other Authors

1994 - Bank's World - Conserving India's Biodiversity Through Participatory Ecodevelopment.

A critical assessment of the then ongoing India Ecodevelopment Project, covering 10 national parks and sanctuaries, authored by a World Bank consultant. DownloadSecond Survey of National Parks and Sanctuaries in India : 1998-2003

Conservation of Wildlife - Second Survey of National Parks and Sanctuaries in India : 1998-2003

Second Survey of the Management of National Parks and Sanctuaries in India

A proposal was sent in and duly approved by the MoEF. A contract was signed with the MOEF in 1998 to conduct this survey over a period of three years (1998-2001), supported by a World Bank grant to the MoEF.

This survey, though similar in methodology and approach to the earlier survey, also sought to expand the scope and collect, compile, and analyse information on aspects other than those studied in the first survey. It also sought to build up a photographic database, and to analyse population data in and around a sample of PAs.

The survey was carried out, as proposed, between 1998 and 2001. The report was submitted to the MOEF in 2001.

We were fortunate to have had, at the IIPA, a highly motivated and competent research team, some of whom had also been members of the research team that had conducted the first survey. Among the senior members there was Vasumathi Sankaran, who was a geographer by training, and had been a member of the wildlife research team at the IIPA since the early 1990s. In age, she was the senior most member of the team and, as such, was the only team member who was addressed formally as Mrs Sankaran (soon abbreviated to Mrs S), while the rest of us were referred to by our first name.

Another senior member of the team was Tara Gandhi, who was a biologist and a wild lifer by training. Raman Mehta, who had been a part of the first survey team, Vishaish Uppal, who had joined the IIPA team in the early 1990s, and Prabhakar Rao, who was a professor at the University of Delhi and assisted in an honorary capacity, were some of the other senior members. In 2001, soon after submitting the report, I left the IIPA and joined as honorary director of the Centre for Equity Studies (CES), New Delhi. Vishaiah Uppal, Salim Qureshi and Arpan Sharma, who were members of the team at IIPA, also shifted to the CES.

Over the next year or so we received a lot of feedback on our 2001 report, and also got back many more filled-in questionnaires from those national parks and sanctuaries that had not responded in time, and therefore whose data could not be included in our 2001 report. It was, therefore, decided to upgrade our 2001 report by taking into consideration the various feedback received and also incorporating the data from the additional questionnaires received. The updated and revised version of the report was submitted to the MoEF, from the CES, in 2003, and is the version that is being included here.

Unfortunately, despite containing much information that would have been of a wider public interest, our reports were never made public. We ourselves were bound by a clause in our agreement which prohibited us from making any information public for a period of 3 years. Much before the 3 years were over, we had all got involved with other things (I with the right to information movement), and therefore these reports remained unpublished. We are trying to right that wrong now, even though much of what these reports contain might now be of historical interest only. Nevertheless, we are hoping that their publication might motivate someone or some institution to initiate a third survey, by a fresh research team, that could properly analyse what has changed, for better or worse, in the management status of national parks and sanctuaries in India over the last nearly 20 years.

Shekhar Singh

Yet to be uploaded:

Directories of NPS containing PA Profiles, Maps, & Photographs